the gestures we use when talking to highlight or accentuate what we are saying are called

Chapter 11. Emotions and Motivations

11.1 The Experience of Emotion

Learning Objectives

- Explicate the biological feel of emotion.

- Summarize the psychological theories of emotion.

- Give examples of the ways that emotion is communicated.

The most fundamental emotions, known every bit the bones emotions, are those of anger, cloy, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise. The basic emotions accept a long history in human evolution, and they accept adult in large part to help us make rapid judgments most stimuli and to apace guide appropriate behaviour (LeDoux, 2000). The basic emotions are determined in big part past one of the oldest parts of our brain, the limbic system, including the amygdala, the hypothalamus, and the thalamus. Because they are primarily evolutionarily determined, the bones emotions are experienced and displayed in much the same way across cultures (Ekman, 1992; Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002; Fridland, Ekman, & Oster, 1987), and people are quite accurate at judging the facial expressions of people from different cultures. View "Video Clip: The Basic Emotions," to run into a sit-in of the basic emotions.

Spotter: "Recognize Basic Emotions" [YouTube]: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=haW6E7qsW2c

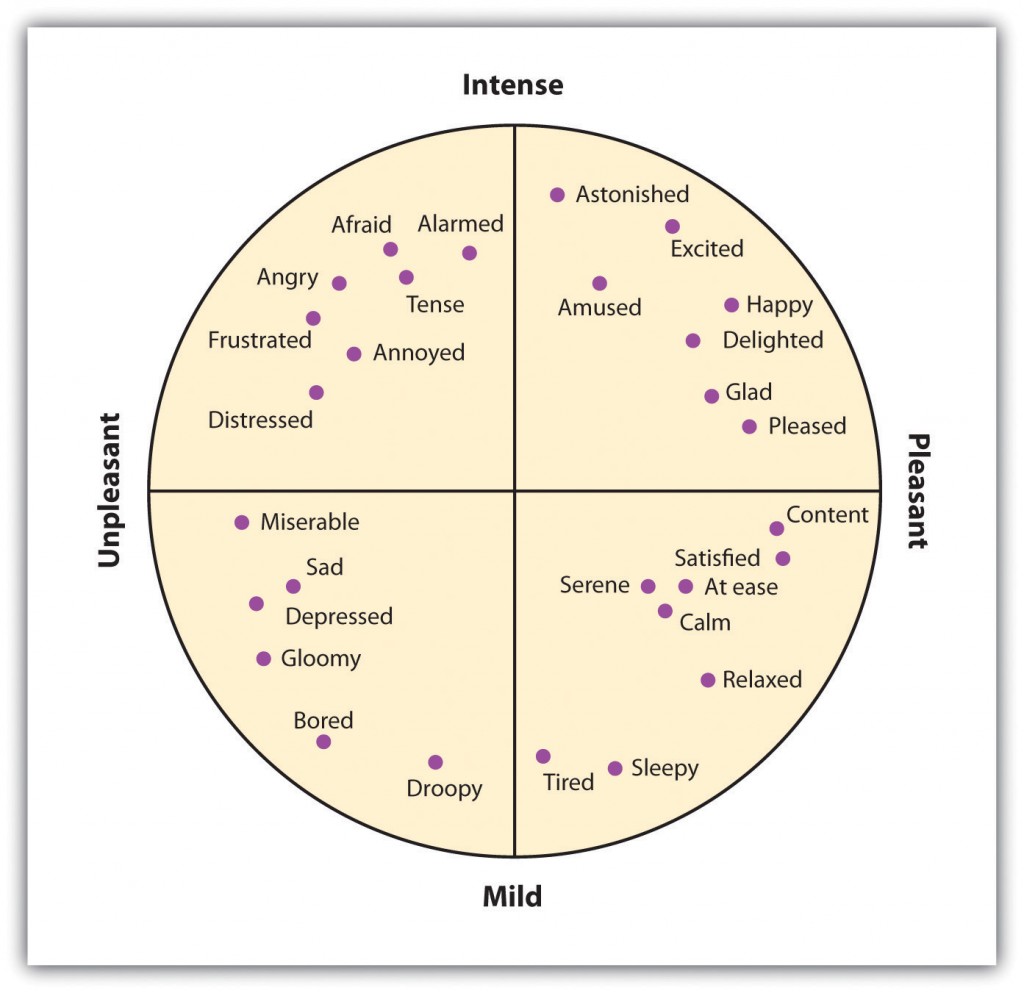

Non all of our emotions come from the former parts of our encephalon; we besides translate our experiences to create a more complex assortment of emotional experiences. For case, the amygdala may sense fear when it senses that the body is falling, merely that fear may be interpreted completely differently (perhaps even every bit excitement) when we are falling on a roller-coaster ride than when we are falling from the sky in an plane that has lost power. The cognitive interpretations that back-trail emotions— known as cerebral appraisal— allow united states of america to feel a much larger and more than complex set of secondary emotions, as shown in Figure 11.2, "The Secondary Emotions." Although they are in large part cognitive, our experiences of the secondary emotions are determined in office by arousal (on the vertical centrality of Figure eleven.2, "The Secondary Emotions") and in part by their valence— that is, whether they are pleasant or unpleasant feelings (on the horizontal axis of Figure 11.2, "The Secondary Emotions"),

When y'all succeed in reaching an important goal, you might spend some time enjoying your secondary emotions, perhaps the experience of joy, satisfaction, and contentment. Merely when your close friend wins a prize that you thought yous had deserved, you might as well experience a variety of secondary emotions (in this case, the negative ones) — for instance, feeling angry, sad, resentful, and aback. You might mull over the event for weeks or even months, experiencing these negative emotions each time you remember nigh information technology (Martin & Tesser, 2006).

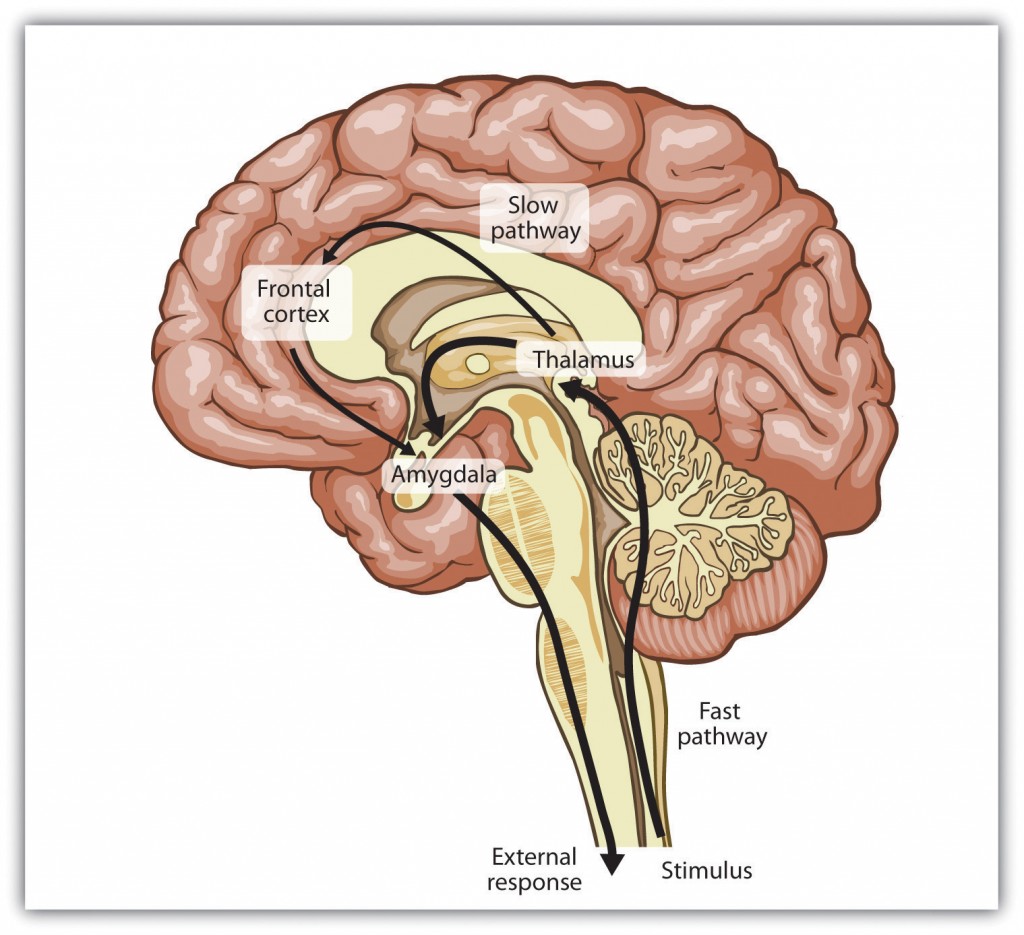

The distinction betwixt the primary and the secondary emotions is paralleled by two brain pathways: a fast pathway and a slow pathway (Damasio, 2000; LeDoux, 2000; Ochsner, Bunge, Gross, & Gabrieli, 2002). The thalamus acts as the major gatekeeper in this procedure (Figure 11.three, "Slow and Fast Emotional Pathways"). Our response to the basic emotion of fear, for instance, is primarily determined past the fast pathway through the limbic organisation. When a car pulls out in front end of us on the highway, the thalamus activates and sends an immediate message to the amygdala. We quickly motion our foot to the brake pedal. Secondary emotions are more than adamant by the slow pathway through the frontal lobes in the cortex. When nosotros stew in jealousy over the loss of a partner to a rival or recollect our win in the large lawn tennis lucifer, the process is more complex. Information moves from the thalamus to the frontal lobes for cognitive assay and integration, and so from there to the amygdala. Nosotros experience the arousal of emotion, but it is accompanied by a more complex cerebral appraisal, producing more refined emotions and behavioural responses.

Although emotions might seem to you lot to be more than frivolous or less important in comparison to our more than rational cognitive processes, both emotions and cognitions tin can aid us make effective decisions. In some cases we take activeness subsequently rationally processing the costs and benefits of different choices, simply in other cases we rely on our emotions. Emotions become specially important in guiding decisions when the alternatives between many complex and alien alternatives nowadays u.s.a. with a loftier degree of doubt and ambiguity, making a complete cognitive analysis difficult. In these cases we often rely on our emotions to make decisions, and these decisions may in many cases exist more than accurate than those produced by cerebral processing (Damasio, 1994; Dijksterhuis, Bos, Nordgren, & van Baaren, 2006; Nordgren & Dijksterhuis, 2009; Wilson & Schooler, 1991).

The Cannon-Bard and James-Lange Theories of Emotion

Recall for a moment a state of affairs in which y'all have experienced an intense emotional response. Possibly you woke upward in the middle of the night in a panic considering yous heard a noise that made y'all think that someone had broken into your house or apartment. Or maybe you were calmly cruising down a street in your neighbourhood when some other automobile suddenly pulled out in front of you lot, forcing you to slam on your brakes to avoid an accident. I'chiliad sure that you call back that your emotional reaction was in large office physical. Perhaps you recall existence flushed, your centre pounding, feeling sick to your stomach, or having trouble breathing. Y'all were experiencing the physiological part of emotion — arousal — and I'm sure you have had similar feelings in other situations, perhaps when y'all were in love, angry, embarrassed, frustrated, or very sad.

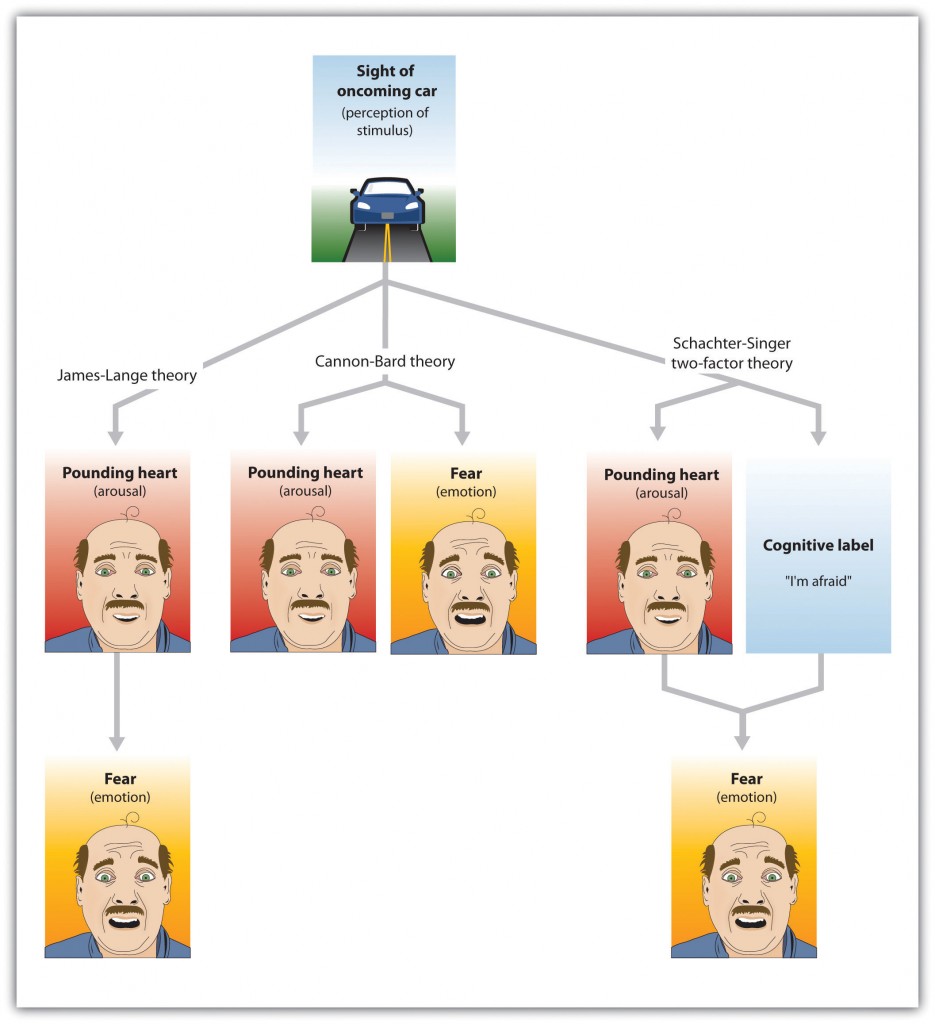

If yous think dorsum to a strong emotional experience, you might wonder nigh the society of the events that occurred. Certainly y'all experienced arousal, just did the arousal come before, after, or along with the experience of the emotion? Psychologists have proposed 3 dissimilar theories of emotion, which differ in terms of the hypothesized role of arousal in emotion (Effigy eleven.4, "Three Theories of Emotion").

If your experiences are similar mine, as you reflected on the arousal that you accept experienced in strong emotional situations, you probably thought something like, "I was afraid and my eye started beating like crazy." At least some psychologists agree with this interpretation. According to the theory of emotion proposed by Walter Cannon and Philip Bard, the feel of the emotion (in this instance, "I'm afraid") occurs alongside the experience of the arousal ("my heart is chirapsia fast"). According to the Cannon-Bard theory of emotion, the feel of an emotion is accompanied past physiological arousal. Thus, according to this model of emotion, every bit nosotros get enlightened of danger, our heart rate as well increases.

Although the idea that the feel of an emotion occurs alongside the accompanying arousal seems intuitive to our everyday experiences, the psychologists William James and Carl Lange had another idea about the role of arousal. According to the James-Lange theory of emotion, our experience of an emotion is the result of the arousal that we feel. This arroyo proposes that the arousal and the emotion are not contained, but rather that the emotion depends on the arousal. The fright does not occur along with the racing heart simply occurs because of the racing heart. As William James put information technology, "We feel sorry considering nosotros cry, aroused considering we strike, afraid because nosotros tremble" (James, 1884, p. 190). A central aspect of the James-Lange theory is that different patterns of arousal may create different emotional experiences.

At that place is research evidence to support each of these theories. The operation of the fast emotional pathway (Figure 11.4, "Deadening and Fast Emotional Pathways") supports the idea that arousal and emotions occur together. The emotional circuits in the limbic organisation are activated when an emotional stimulus is experienced, and these circuits quickly create corresponding concrete reactions (LeDoux, 2000). The process happens and then rapidly that it may feel to the states as if emotion is simultaneous with our concrete arousal.

On the other manus, and as predicted by the James-Lange theory, our experiences of emotion are weaker without arousal. Patients who have spinal injuries that reduce their experience of arousal also report decreases in emotional responses (Hohmann, 1966). There is also at least some back up for the idea that different emotions are produced by unlike patterns of arousal. People who view fearful faces show more than amygdala activation than those who picket aroused or blithesome faces (Whalen et al., 2001; Witvliet & Vrana, 1995), we experience a red face and flushing when nosotros are embarrassed but not when we experience other emotions (Leary, Britt, Cutlip, & Templeton, 1992), and different hormones are released when we experience compassion than when we feel other emotions (Oatley, Keltner, & Jenkins, 2006).

The Two-Factor Theory of Emotion

Whereas the James-Lange theory proposes that each emotion has a different pattern of arousal, the ii-factor theory of emotion takes the opposite approach, arguing that the arousal that we experience is basically the same in every emotion, and that all emotions (including the basic emotions) are differentiated only by our cerebral appraisal of the source of the arousal. The two-cistron theory of emotion asserts that the experience of emotion is determined past the intensity of the arousal nosotros are experiencing, simply that the cerebral appraisement of the state of affairs determines what the emotion volition exist. Considering both arousal and appraisal are necessary, nosotros can say that emotions have two factors: an arousal factor and a cognitive factor (Schachter & Vocaliser, 1962):

emotion = arousal + cognition

In some cases it may exist difficult for a person who is experiencing a high level of arousal to accurately determine which emotion he or she is experiencing. That is, the person may be certain that he or she is feeling arousal, only the significant of the arousal (the cognitive gene) may be less clear. Some romantic relationships, for example, have a very loftier level of arousal, and the partners alternatively experience extreme highs and lows in the relationship. I twenty-four hours they are madly in dearest with each other and the side by side they are in a huge fight. In situations that are accompanied by high arousal, people may be unsure what emotion they are experiencing. In the high arousal relationship, for instance, the partners may be uncertain whether the emotion they are feeling is dear, hate, or both at the same time. The trend for people to incorrectly label the source of the arousal that they are experiencing is known as the misattribution of arousal.

In 1 interesting field study by Dutton and Aron (1974), an attractive immature adult female approached individual young men as they crossed a wobbly, long suspension walkway hanging more 200 feet above a river in British Columbia (Effigy 11.v, "Capilano Pause Span"). The woman asked each man to assist her make full out a class questionnaire. When he had finished, she wrote her name and phone number on a slice of paper, and invited him to phone call if he wanted to hear more about the project. More than half of the men who had been interviewed on the bridge later called the adult female. In contrast, men approached past the aforementioned woman on a low, solid bridge, or who were interviewed on the pause bridge past men, called significantly less frequently. The idea of misattribution of arousal can explicate this result — the men were feeling arousal from the peak of the bridge, just they misattributed it every bit romantic or sexual allure to the woman, making them more likely to phone call her.

Research Focus: Misattributing Arousal

If you lot think a chip about your ain experiences of different emotions, and if you consider the equation that suggests that emotions are represented by both arousal and cognition, yous might start to wonder how much was determined by each. That is, do we know what emotion nosotros are experiencing by monitoring our feelings (arousal) or by monitoring our thoughts (cognition)? The bridge study you merely read about might begin to provide you with an answer: The men seemed to exist more influenced by their perceptions of how they should be feeling (their cognition) rather than by how they really were feeling (their arousal).

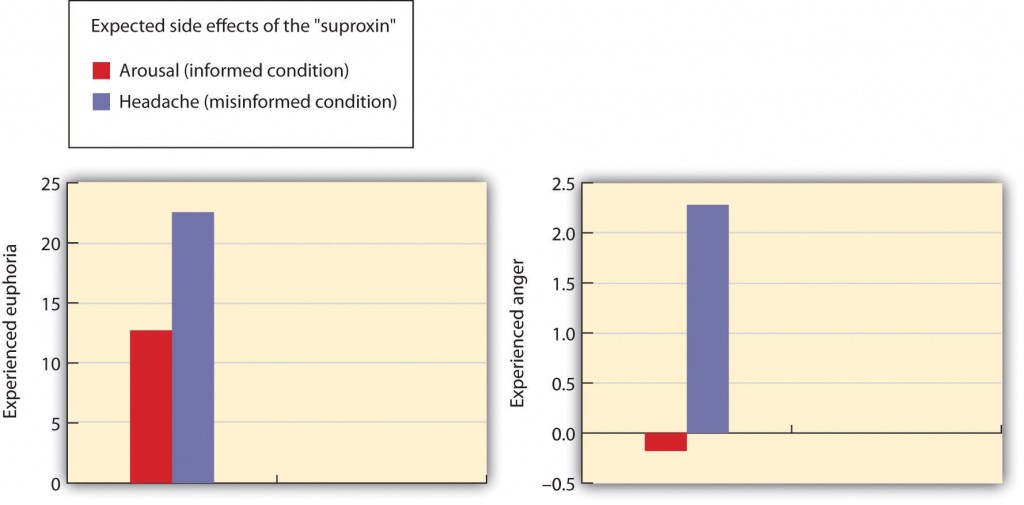

Stanley Schachter and Jerome Vocalist (1962) directly tested this prediction of the two-factor theory of emotion in a well-known experiment. Schachter and Vocalist believed that the cognitive part of the emotion was disquisitional — in fact, they believed that the arousal that we experience could be interpreted as any emotion, provided we had the right label for information technology. Thus they hypothesized that if an individual is experiencing arousal for which there is no immediate explanation, that individual will "label" this state in terms of the cognitions that are created in his or her surroundings. On the other hand, they argued that people who already have a clear label for their arousal would have no need to search for a relevant characterization, and therefore should not experience an emotion.

In the inquiry, male participants were told that they would be participating in a study on the furnishings of a new drug, chosen suproxin, on vision. On the ground of this cover story, the men were injected with a shot of the neurotransmitter epinephrine, a drug that ordinarily creates feelings of tremors, flushing, and accelerated animate in people. The idea was to requite all the participants the experience of arousal.

So, according to random assignment to conditions, the men were told that the drug would make them feel certain ways. The men in the epinephrine informed status were told the truth nigh the effects of the drug — that they would likely feel tremors, their hands would get-go to milk shake, their hearts would start to pound, and their faces might go warm and flushed. The participants in the epinephrine-uninformed condition, however, were told something untrue — that their feet would feel numb, they would take an itching sensation over parts of their body, and they might get a slight headache. The idea was to brand some of the men call up that the arousal they were experiencing was acquired past the drug (the informed condition), whereas others would be unsure where the arousal came from (the uninformed condition).

Then the men were left alone with a confederate who they thought had received the same injection. While they were waiting for the experiment (which was supposedly about vision) to begin, the amalgamated behaved in a wild and crazy manner (Schachter and Singer called it a "euphoric" manner). He wadded upwardly spitballs, flew newspaper airplanes, and played with a hula-hoop. He kept trying to get the participant to bring together in with his games. Then right before the vision experiment was to begin, the participants were asked to indicate their current emotional states on a number of scales. One of the emotions they were asked about was euphoria.

If y'all are following the story, you will realize what was expected: The men who had a label for their arousal (the informed group) would not be experiencing much emotion because they already had a label available for their arousal. The men in the misinformed group, on the other paw, were expected to exist unsure about the source of the arousal. They needed to notice an explanation for their arousal, and the confederate provided i. Every bit you tin run into in Effigy 11.vi ,"Results from Schachter and Vocalist, 1962″ (left side), this is but what they found. The participants in the misinformed condition were more likely to experience euphoria (every bit measured by their behavioural responses with the confederate) than were those in the informed condition.

And then Schachter and Singer conducted some other part of the study, using new participants. Everything was exactly the same except for the behaviour of the confederate. Rather than beingness euphoric, he acted angry. He complained nearly having to complete the questionnaire he had been asked to do, indicating that the questions were stupid and too personal. He ended up trigger-happy upward the questionnaire that he was working on, yelling, "I don't have to tell them that!" Then he grabbed his books and stormed out of the room.

What exercise you think happened in this condition? The answer is the same affair: the misinformed participants experienced more anger (again equally measured by the participant's behaviours during the waiting menses) than did the informed participants. (Effigy eleven.half dozen, "Results from Schachter and Singer, 1962", right side). The idea is that considering cognitions are such strong determinants of emotional states, the same state of physiological arousal could exist labelled in many different ways, depending entirely on the label provided by the social situation. As Schachter and Singer put it: "Given a state of physiological arousal for which an individual has no immediate explanation, he will 'label' this state and draw his feelings in terms of the cognitions bachelor to him" (Schachter & Singer, 1962, p. 381).

Because it assumes that arousal is abiding beyond emotions, the two-factor theory also predicts that emotions may transfer or spill over from one highly arousing result to another. My university basketball squad recently won a basketball title, but subsequently the final victory some students rioted in the streets well-nigh the campus, lighting fires and called-for cars. This seems to be a very strange reaction to such a positive outcome for the university and the students, but information technology tin exist explained through the spillover of the arousal caused by happiness to destructive behaviours. The principle of excitation transfer refers to the phenomenon that occurs when people who are already experiencing arousal from ane issue tend to too experience unrelated emotions more strongly.

In sum, each of the iii theories of emotion has something to back up information technology. In terms of Cannon-Bard, emotions and arousal generally are subjectively experienced together, and the spread is very fast. In support of the James-Lange theory, in that location is at least some evidence that arousal is necessary for the experience of emotion, and that the patterns of arousal are dissimilar for unlike emotions. And in line with the 2-gene model, there is also evidence that we may interpret the aforementioned patterns of arousal differently in different situations.

Communicating Emotion

In addition to experiencing emotions internally, we also express our emotions to others, and we learn most the emotions of others by observing them. This advice process has evolved over time and is highly adaptive. One way that nosotros perceive the emotions of others is through their nonverbal advice, that is, communication, primarily of liking or disliking, that does non involve words (Ambady & Weisbuch, 2010; Andersen, 2007). Nonverbal communication includes our tone of phonation, gait, posture, touch, and facial expressions, and we can often accurately discover the emotions that other people are experiencing through these channels. Table 11.ane, "Some Common Nonverbal Communicators," shows some of the important nonverbal behaviours that we use to limited emotion and some other information (particularly liking or disliking, and authorization or submission).

| [Skip Table] | ||

| Nonverbal cue | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Proxemics | Rules nearly the appropriate use of personal space | Standing nearer to someone tin can express liking or authority. |

| Body appearance | Expressions based on alterations to our trunk | Body building, breast augmentation, weight loss, piercings, and tattoos are ofttimes used to appear more bonny to others. |

| Body positioning and motility | Expressions based on how our trunk appears | A more "open" body position can announce liking; a faster walking speed can communicate say-so. |

| Gestures | Behaviours and signs made with our hands or faces | The peace sign communicates liking; the "finger" communicates boldness. |

| Facial expressions | The variety of emotions that we limited, or attempt to hide, through our face | Grinning or frowning and staring or avoiding looking at the other can express liking or disliking, every bit well as authority or submission. |

| Paralanguage | Clues to identity or emotions contained in our voices | Pronunciation, accents, and dialect can be used to communicate identity and liking. |

Only as there is no universal oral communication, there is no universal nonverbal linguistic communication. For instance, in Canada we limited boldness by showing the middle finger (the finger or the bird). But in Great britain, Republic of ireland, Australia, and New Zealand, the V sign (made with back of the paw facing the recipient) serves a similar purpose. In countries where Spanish, Portuguese, or French are spoken, a gesture in which a fist is raised and the arm is slapped on the bicep is equivalent to the finger, and in Russia, Indonesia, Turkey, and Red china a sign in which the hand and fingers are curled and the thumb is thrust between the center and index fingers is used for the same purpose.

The near important communicator of emotion is the face. The face contains 43 unlike muscles that let information technology to make more than 10,000 unique configurations and to express a wide diversity of emotions. For example, happiness is expressed past smiles, which are created by two of the major muscles surrounding the mouth and the eyes, and anger is created by lowered brows and firmly pressed lips.

In addition to helping united states limited our emotions, the confront also helps u.s.a. experience emotion. The facial feedback hypothesis proposes that the motility of our facial muscles can trigger corresponding emotions. Fritz Strack and his colleagues (1988) asked their research participants to hold a pen in their teeth (mimicking the facial activity of a smile) or between their lips (similar to a frown), so had them charge per unit the funniness of a cartoon. They establish that the cartoons were rated every bit more than amusing when the pen was held in the smiling position — the subjective experience of emotion was intensified by the action of the facial muscles.

These results, and others similar them, show that our behaviours, including our facial expressions, both influence and are influenced by our bear on. We may smile because we are happy, simply we are also happy because nosotros are grinning. And we may stand upwardly straight considering we are proud, but we are proud because nosotros are standing upwardly straight (Stepper & Strack, 1993).

Key Takeaways

- Emotions are the normally adaptive mental and physiological feeling states that direct our attention and guide our behaviour.

- Emotional states are accompanied past arousal, our experiences of the bodily responses created past the sympathetic segmentation of the autonomic nervous organization.

- Motivations are forces that guide behaviour. They tin be biological, such equally hunger and thirst; personal, such as the motivation for achievement; or social, such as the motivation for credence and belonging.

- The most fundamental emotions, known as the bones emotions, are those of anger, cloy, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise.

- Cerebral appraisal likewise allows usa to experience a diverseness of secondary emotions.

- According to the Cannon-Bard theory of emotion, the feel of an emotion is accompanied by physiological arousal.

- According to the James-Lange theory of emotion, our experience of an emotion is the event of the arousal that we experience.

- According to the two-factor theory of emotion, the experience of emotion is adamant by the intensity of the arousal nosotros are experiencing, and the cerebral appraisal of the situation determines what the emotion will be.

- When people incorrectly label the source of the arousal that they are experiencing, we say that they have misattributed their arousal.

- Nosotros express our emotions to others through nonverbal behaviours, and we learn nigh the emotions of others by observing them.

Exercises and Disquisitional Thinking

- Consider the 3 theories of emotion that we take discussed and provide an case of a situation in which a person might experience each of the three proposed patterns of arousal and emotion.

- Describe a time when you used nonverbal behaviours to limited your emotions or to find the emotions of others. What specific nonverbal techniques did y'all use to communicate?

References

Ambady, N., & Weisbuch, M. (2010). Nonverbal behavior. In S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & Yard. Lindzey (Eds.),Handbook of social psychology (5th ed., Vol. ane, pp. 464–497). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Andersen, P. (2007).Nonverbal communication: Forms and functions (2nd ed.). Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

Damasio, A. (2000).The feeling of what happens: Body and emotion in the making of consciousness. New York, NY: Mariner Books.

Damasio, A. R. (1994).Descartes' error: Emotion, reason, and the human encephalon. New York, NY: Grosset/Putnam.

Dijksterhuis, A., Bos, M. W., Nordgren, 50. F., & van Baaren, R. B. (2006). On making the correct choice: The deliberation-without-attention effect.Science, 311(5763), 1005–1007.

Dutton, D., & Aron, A. (1974). Some evidence for heightened sexual attraction under atmospheric condition of high anxiety.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, xxx, 510–517.

Ekman, P. (1992). Are there basic emotions?Psychological Review, 99(3), 550–553.

Elfenbein, H. A., & Ambady, Due north. (2002). On the universality and cultural specificity of emotion recognition: A meta-assay.Psychological Bulletin, 128, 203–23.

Fridlund, A. J., Ekman, P., & Oster, H. (1987). Facial expressions of emotion. In A. Siegman & Southward. Feldstein (Eds.),Nonverbal behavior and communication (2nd ed., pp. 143–223). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hohmann, G. W. (1966). Some effects of spinal cord lesions on experienced emotional feelings.Psychophysiology, 3(2), 143–156.

James, W. (1884). What is an emotion?Listen, 9(34), 188–205.

Leary, M. R., Britt, T. W., Cutlip, W. D., & Templeton, J. L. (1992). Social blushing.Psychological Bulletin, 112(3), 446–460.

LeDoux, J. East. (2000). Emotion circuits in the brain.Almanac Review of Neuroscience, 23, 155–184.

Martin, L. L., & Tesser, A. (2006). Extending the goal progress theory of rumination: Goal reevaluation and growth. In L. J. Sanna & E. C. Chang (Eds.),Judgments over fourth dimension: The interplay of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (pp. 145–162). New York, NY: Oxford Academy Press.

Nordgren, Fifty. F., & Dijksterhuis, A. P. (2009). The devil is in the deliberation: Thinking likewise much reduces preference consistency.Periodical of Consumer Research, 36(1), 39–46.

Oatley, K., Keltner, D., & Jenkins, J. Grand. (2006).Understanding emotions (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Ochsner, Thousand. Due north., Bunge, S. A., Gross, J. J., & Gabrieli, J. D. E. (2002). Rethinking feelings: An fMRI report of the cognitive regulation of emotion.Periodical of Cognitive Neuroscience, 14(eight), 1215–1229.

Russell, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of bear on. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 1161–1178.

Schachter, S., & Vocalist, J. (1962). Cerebral, social, and physiological determinants of emotional land.Psychological Review, 69, 379–399.

Stepper, S., & Strack, F. (1993). Proprioceptive determinants of emotional and nonemotional feelings.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(ii), 211–220.

Strack, F., Martin, 50., & Stepper, S. (1988). Inhibiting and facilitating conditions of the human smiling: A nonobtrusive test of the facial feedback hypothesis.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(5), 768–777. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.v.768

Whalen, P. J., Shin, L. M., McInerney, Southward. C., Fischer, H., Wright, C. I., & Rauch, Due south. L. (2001). A functional MRI study of human amygdala responses to facial expressions of fearfulness versus anger.Emotion, ane(1), 70–83;

Wilson, T. D., & Schooler, J. W. (1991). Thinking too much: Introspection tin can reduce the quality of preferences and decisions.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(2), 181–192.

Witvliet, C. 5., & Vrana, S. R. (1995). Psychophysiological responses as indices of affective dimensions.Psychophysiology, 32(5), 436–443.

Prototype Attributions

Figure 11.2: Adapted from Russell, 1980.

Effigy 11.5: Capilano pause bridge by Goobiebilly (http://eatables.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Capilano_suspension_bridge_-one thousand.jpg) used nether CC-By two.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en).

Effigy xi.6: Adjusted from Schachter & Singer, 1962.

Long Descriptions

| Level of Arousal | Unpleasant | Pleasant |

|---|---|---|

| Mild |

|

|

| Intense |

|

|

[Return to Figure eleven.two]

Source: https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontopsychology/chapter/10-1-the-experience-of-emotion/

Postar um comentário for "the gestures we use when talking to highlight or accentuate what we are saying are called"